One Time and Again Music Album

On Wednesday, June 10, the Grammys dropped the term "urban" from what was formerly known as the Best Urban Contemporary Album category, and this relatively new award was rebranded as All-time Progressive R&B Album. Republic Records, the characterization that represents Nicki Minaj, The Weeknd and Drake, is amidst several other record companies that announced they as well will no longer utilise the term in describing everything from music genres to employee titles.

More and more artists and executives take started calling for the removal of "urban" as a characterization in the music industry, including the winner of the 2022 Grammy for Best Rap album — Tyler, the Creator — who described the term every bit a "politically right way to say the Due north-word." Although it once had its place in the radio industry — all the way back in the 1970s — "urban" today bears racial undertones that amerce the Blackness artists information technology supposedly represents. It's time the music industry does away with this term completely, considering, in the words of Democracy Records, "urban" has "developed into a generalization of Blackness people" that does goose egg but reinforce stereotypes.

Where Did "Urban" Come up From?

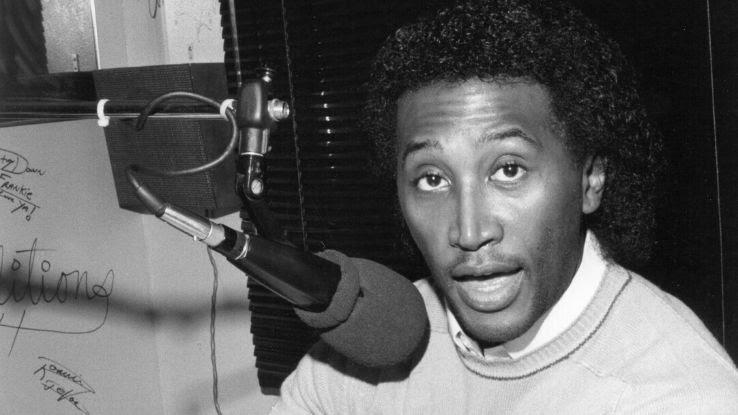

DJ Frankie Crocker is often credited equally being the first person to use the term "urban" to describe music. In the mid 1970s, Crocker worked every bit a DJ and radio program director at New York'due south so-new station, WBLS-FM. Although his career at the station took off during the height of disco — Crocker was a frequent Studio 54 fixture and in one case rode into the gild on a white horse — he preferred playing a various mix of music from an array of genres that included everything from funk, jazz and R&B to big band, reggae and an emerging style that would somewhen have the world past tempest: hip-hop.

To describe the unique blend of genres that he played on the station, Crocker used the phrase "urban contemporary," likely cartoon from the term "urban radio," which referred to Black-run radio stations during the Civil Rights era that used clandestine codes to tell protestors where to run across for marches. He used his platform to amplify Blackness voices, equally many of the artists he played during his sets were African American and Caribbean, and people began positively associating the phrase "urban contemporary" with the Blackness artists whose songs oft appeared on the station. While initially "urban contemporary" described an heady melange of musical styles on one radio show, others took the term and ran with it. Stations across the country in other large cities like Detroit began using the phrase when they played music like to Crocker's sets. Somewhen, equally things tend to do when someone realizes in that location's money to exist made, "urban contemporary" started to change in meaning to commodify, not represent, Black artists and their art.

Music executives realized they could begin marketing what they saw as "Blackness music" to white people without explicitly using words that referred to race, which staved off discomfort in an era when desegregation was notwithstanding taking identify and white flight was dramatically irresolute the faces of American cities — which, perhaps ironically, were considered "urban" areas. In social club to capitalize on this, executives started calling the music Crocker and others were playing "urban," an cryptic-sounding term that lumped a multifariousness of genres under one umbrella term and did little for representation. While this was arguably helpful in that it allowed companies to market place music by Black artists to much wider audiences, it also immune them to market to much whiter audiences — at a cost.

Labeling music "urban" helped make white listeners and "white executives more than comfortable," Billboard executive Gail Mitchell told NPR. While creating new "urban" divisions at record labels and radio stations paved the way for Black executives to have on burgeoning roles finding and helping Black artists, it besides immune white leaders at those organizations to essentially "[box] those executives in. [Urban] was a bad word to the white gatekeepers," Mitchell notes. As the term spread during the 1980s, information technology became a catchall word that implicitly referred to any music by Black people — no matter what the genre of a Black artist happened to exist, their music was simply "urban." And at that point, the word had picked upwardly enough steam to become mainstream.

Why Is It Problematic to Describe Music as "Urban"?

The term "urban" beingness used to describe musical genres wasn't problematic when Crocker applied information technology at WBLS-FM; it was celebratory and highlighted the diversity of the urban metropolis — New York City — that the station called home. Merely "urban" became a manner of saying "Black" without proverb Blackness, and people started using it to refer to all Blackness artists, regardless of their genres. The give-and-take effectively blurred and even erased the identities and differences of the artists (whose creativity should've been honored) in club to make sure the culturally dominant segment of the population didn't feel uncomfortable listening to sure music.

It became a tool of oppression in the music industry, putting limits on Blackness artists' inventiveness and Black executives' agency — "they [were] told to stay in their lane," which meant they needed to stick to the genres under the urban umbrella, Mitchell notes. "Urban" became a tool for relegating many Black artists to their ain separate niche of music, essentially segregating them to i category and preventing their work from gaining recognition in genres that would've put them on the same level as white artists. This is seen in the way the give-and-take has been codified by its utilise as a label in some very prominent ways. At that place are the Grammy awards titles, of course, but record labels have "urban" divisions and radio stations are notwithstanding referred to equally "urban" when describing the music they play. Even clothing stores are often referred to as "urban" when they sell styles that Black musicians take made popular.

Using the give-and-take "urban" to describe music genres has become a lazy way to group together much of today'due south music by Black artists. Information technology creates the impression of a Black-artist monolith that fails to honour, or fifty-fifty take into account, the richly varied origins and talents and the various voices and perspectives of Blackness singers, songwriters, composers, musicians, producers and others who have fought tirelessly to secure their places in the music industry. "Urban" racializes music by group together artists by race. It doesn't affair how dissimilar reggae is from hip-hop or R&B is from rap; it's all grouped together as "urban."

The term is problematic considering information technology marginalizes Black artists, setting them on their own exterior the rest of the genres that their music really encompasses. It keeps them on the periphery of the industry and obscures their true impact on music. Historically, it referenced Blackness without naming it, implying that at that place was something "wrong" with using the discussion "Blackness" because such an overt reference would make white listeners uncomfortable, and those are dangerous waters to tread. It unfairly prevents artists from accessing genres where they could arguably find more success. Despite this, some artists and executives worry about "urban" eventually disappearing.

Are There Downsides to Removing "Urban"?

Although a number of artists, executives and other industry-next professionals have criticized the continued utilize of "urban," some aren't equally excited to see it go. Instead, they're fearful about what information technology could mean for representation. An anonymous source at Republic Records told Elias Leight of Rolling Rock that some Black employees were worried about the alter, proverb, "Their fright is, does getting rid of the term take away our spot?" Leight goes on to note that, "for decades, 'urban' departments have been the labels' only condom haven for Black executives. If 'urban' disappears, what protections remain?" Others worry that discontinuing the word's use is merely a symbolic gesture and that it won't actually change how a label operates — that labels will continue to grouping Black artists together based on their race.

These concerns are real and valid, peculiarly in the context of a word that has historically been used to erase Blackness identities from music. As record labels and other industry groups begin navigating a world without "urban," information technology'due south of utmost importance that they continue intentionally creating space for Black employees and executives to ensure their voices are heard and their representation exists.

The Grammys Drib "Urban" — Sort Of

In a promising step forwards, and perhaps arising from conversations nigh race that take arisen post-obit protests over the murder of George Floyd, the Grammys opted to modify the proper noun of one award that previously used the term. However, "urban" is still in use in another accolade title. The Grammy Laurels for All-time Latin Popular, Rock or Urban Anthology has undergone some changes and merged with other categories but continues to include the term in its new Best Latin Pop or Urban Honor championship. What exactly is meant by "urban" in this context — and why is it nonetheless at that place? Could in that location exist split awards for Latin Popular, Latin Rock and whatever genre "Latin Urban" might be instead of, again, grouping relatively disparate musical styles together because they're by Latinx artists?

That "urban" was dropped in one category but not another is an interesting, if somewhat unexplainable, development. This could hateful that the phasing out of the term'due south utilize will be gradual. On the other hand, information technology could mean that there'southward not a consensus among those in the industry who are involved in these decisions, and they need to become on the same page. This inconsistency in naming awards also brings upward the question of whether the changes were only made to placate critics with the goal of reinstating normalcy, non of setting an example for a step toward positive change. At this early on stage, only time volition tell.

What Will the Time to come Hold for "Urban"?

The music manufacture and world at large have undergone many changes since DJ Frankie Crocker first coined "urban contemporary." When Crocker was dissemination in the 1970s, the office of a DJ was so much more than of import to music culture than it is today. People didn't have the pick to load up Spotify or Apple Music and cull a single song or genre to heed to. DJs curated their playlists using a variety of different styles and picked the music they felt would appeal most to their audiences. DJs alone were the ones who could select and mix the music that played on the radio, and group several genres together fabricated far more sense in the 1970s and '80s than it does today.

Only things are different now, and information technology'south time for the music industry to play a picayune catchup in a world where it's gotten used to dictating trends. The genres grouped together as "urban" are then diverse that often the only thing they have in mutual is the race of many of the artists, and information technology's fourth dimension for the music manufacture to acknowledge that variety in a way that'southward more meaningful. Forcing these genres nether the same category for the sake of an award tin can feel insulting to the artists involved and to artistry itself. It's time for the industry to remove "urban" from its vocabulary completely and first celebrating private genres. And this needs to happen while the industry uses its power to secure spots for the Black executives currently working in "urban" departments — and the many more than people of color information technology needs to hire in order to award the diversity it's been capitalizing on for decades.

Source: https://www.ask.com/entertainment/grammys-removes-word-urban?utm_content=params%3Ao%3D740004%26ad%3DdirN%26qo%3DserpIndex

0 Response to "One Time and Again Music Album"

Post a Comment